First posted at the Ark blog.

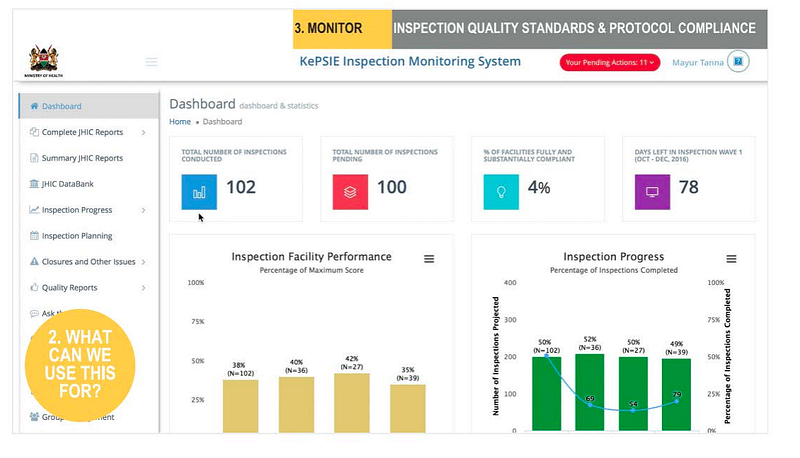

If the Adam Smith Institute can reclaim the pejorative label ‘neoliberal’, maybe we should be reclaiming the pejorative ‘global education reform movement (GERM)’? Aside from the unfortunate acronym, it’s actually a pretty good description of the cluster of people and organisations trying to shake things up a bit and do things differently in global education policy.Here’s a round-up of some of my highlights from the GERM in 2017. There has been some solid progress in documenting the scale of the global learning crisis, and steps towards building the kind of global data infrastructure we need to measure the SDG on learning. In 2018 I’d like to see more measurement, and also more experimentation. The conversation in education still needs to shift some more away from “we know how to fix this just give us the cash” to the maybe slightly less compelling but more honest “this is a crisis that needs fixing, we know where we want to get to but we don’t yet know how to get there, so we’re going to throw everything we have at it, and measure the hell out of everything so we can learn and course correct until we get there.”

---

January - The big global education jamboree kicks off each year with the Education World Forum in London, not to be confused with the World Education Forum, the Global Education and Skills Forum, or the World Global Forum for Education and Children Who Can’t Read Good (I might have made up the last one).

George K. Werner, the Minister of Education in Liberia, publishes the first of many articleswritten in 2017 on the controversial Partnership Schools programme. “Less than 60% of school-aged children in Liberia are in school … Those who do attend school may not fare much better: among adult women who reached fifth grade in Liberia, less than 20% can read a single sentence.”

In Colombia, 22 of Bogota’s ‘Concession schools’ (PPP schools, like charters in the US or academies in the UK) re-open for another 10 year contract, after their last contract ended and was renegotiated last year.

February - The second, annual meeting of the Global Schools Forum is launched. The GSF event is a gathering of non-state school operators working in low- and middle-income countries and targeting the bottom half of the income distribution, comes together, networks, and shares ideas. I blogged about my general feelings of inferiority whilst rubbing shoulders with all these inspiring people who have set up their own schools here. Watch out for GSF in 2018, as the annual meeting promises to be even bigger and better!

March - The next big global education jamboree in the calendar is the Global Education and Skills Forum in Dubai. Daisy Christodoulou blogged about how she remarkably managed to win a debate in favour of teaching kids facts in the age of Google. She also reported on a fascinating debate about teaching global versus national values. If you don’t know Daisy, 2007 University Challenge champion, you should really read this superb feature profile by Laura McInerney in SchoolsWeek.

As we don’t (yet) have very good data on actual learning in many developing countries, a growing movement is spreading the idea started by Pratham in India of recruiting citizen-volunteers to administer simple learning assessments on a mass scale. The “People’s Action for Learning” (PAL) network held its 5th annual meeting in Mexico, welcomed Nepal as the newest member, reaching a total of 16 countries.

April - The Government of the Punjab province in Pakistan contracts out the management around 1,000 failing schools to private operators, bringing the total for the first year of the Public School Support Programme (PSSP) to almost 5,000 schools - that’s about how many schools have been converted to Academies in the UK over 16 years!

June - The great and the good of global education research meets in Washington DC for the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) conference (report here). Ark EPG launches its Rigorous Review of the evidence on public-private partnerships in education in developing countries (post 2009). The review only found 22 studies that met the quality criteria, but of these most were positive.

In the Philippines, the senior high school (Grade 11 and 12) voucher programme enters its second year - over 600,000 students started in Grade 11 through the programme last year.

July - The Western Cape government drafted legislation for the creation of a new independent School Evaluation Authority.

Amitav Virmani, CEO of the Education Alliance, blogged an update on South Delhi Municipal Government’s Partnership Schools. Starting with one (Ark) school in 2015, the programme is now up to 29 schools, “While the rest of the system lost 12,000 students last year, these schools doubled their enrolment to 1600 children.”

Education International and ActionAid publishes a critical research report on Partnership Schools for Liberia based on qualitative research in “up to” 20 schools (how many was it?), just 2 months before the actual results would be published from the large-scale RCT which assessed the actual learning of thousands of children in 185 schools, which everyone agreed was a “really helpful” contribution to the dialogue.

August - The 3rd annual “State of the Nation” report on India’s Right to Education Act (Section 12(1)(c)) comes out, highlighting that 5 years after the policy was confirmed, still only 1 in 3 states in India have accessed any federal funding for the programme. This year’s report dives into some of the details of the private school lotteries in states that are actually implementing the policy at scale, including Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan.

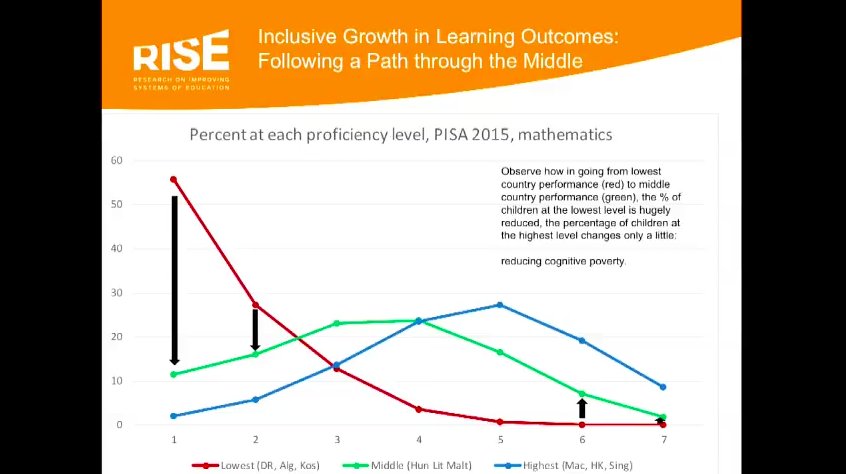

September - In a major contribution to the all-too-sparse global data on learning, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics released a new global indicator for reading proficiency (based on PIRLS, TIMSS, and SACMEQ) - finding a headline figure of 387 million children worldwide who can’t read, and of these 2 in 3 are actually attending school, they just aren’t learning.

Results from the 1st year of Partnership Schools for Liberia (PSL) evaluation comes in, with both supporters and critics hailing the results as proving them right. On average PSL schools saw solid improvements in teaching and learning, great for the first year of a pilot, but with some operators spending large amounts of money they raised, and weaknesses in contracting allowing “the largest operator” to move some children and teachers out of their schools.

The World Bank publishes its first ever annual World Development Report focused entirely on education. The report carried many of the same themes as the RISE research programme - highlighting the global learning crisis and calling for more learning assessment and for systemic reforms to try and address the crisis in quality.

UNESCO publishes its flagship Global Education Monitoring Report on the topic of accountability, and easily came away with the prize for best illustrated report.

As part of the above-mentioned South Delhi Government Partnership Schools programme, 2 new Ark-backed schools open this September as part of a plan to grow to 10 schools by 2022.

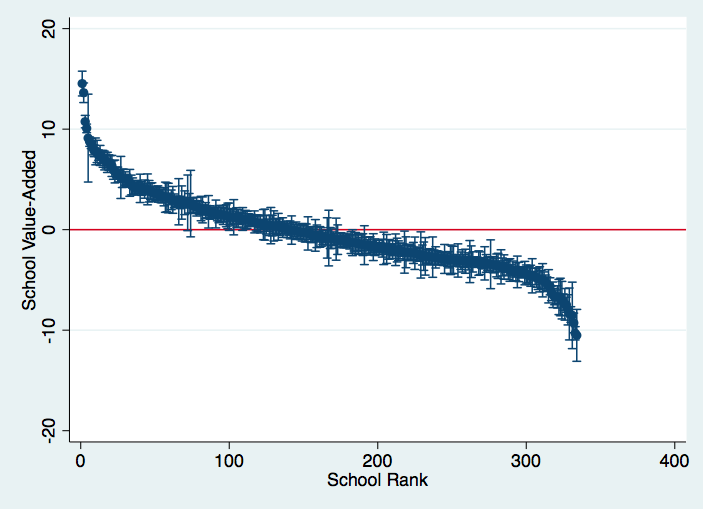

October - The Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB) announces that starting in 2018, a new measure of secondary school effectiveness will be published based on value-added. This is a fairer way to compare schools than just looking at the level of test scores, which are much more heavily influenced by home background. This will make Uganda the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to use value-added to judge school quality.

November - The UK Parliament International Development Committee publishes its reporton DFID’s work on global education. The report welcomed the results from the PSL study and called for more research into non-state schooling, as well as backing the RISE research programme focused on systems of accountability.

In South Africa, an op-ed-war breaks on South Africa’s collaboration school project, with Equal Education calling the pilot illegal, undemocratic, and unaccountable, to which Education Minister Debbie Shafer replies “We will not be deterred by the likes of Equal Education, who cannot come up with any feasible plan to address the inequalities that still exist as a result of our apartheid legacy,” and David Harrison from the DG Murray Trust adds that the programme “gives parents the right to decide whether or not they want to be part of the experiment.”

At the World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE) in Doha, more progress was made on the nascent “global education ecosystem” project being launched by the Education Commission, R4D, Teach for All, Asia Society, and Brookings. At the exact same time, Pratham were putting these ideas into action, sharing their promising “Teaching at the right level” programme with participants from 12 countries, an idea which according to JPAL is “the most consistently effective at improving learning” from all of their learning-focused RCTs.

December - Just in time for Christmas, the latest international test score results are published - this time in reading from PIRLS. These tests included no low-income countries, and just a handful of lower-middle income countries: Egypt, Georgia, and Morocco. The worst performing country though was upper-middle income South Africa, where 8 out of 10 children can’t read. Nic Spaull provided extensive coverage on very depressing news for South Africa on his must-read blog.

What did I miss?