This post first appeared on the RISE website

Why do Vietnam school children score over 100 points better on comparable tests than the average for low-income countries?

Vietnam is basically the only low-income country in any of the internationally comparable tests that performs at the same level as rich countries. Vietnam is a massive outlier, performing substantially better than should be expected for a country at that level of income. Rich OECD countries such as the UK and US flock to see the top performing places in the world on the PISA test to try and understand what is so special about education systems in Shanghai and Finland that enables them to perform 100 points better than the OECD average. Vietnam scores over 100 points better than the average for low-income countries.

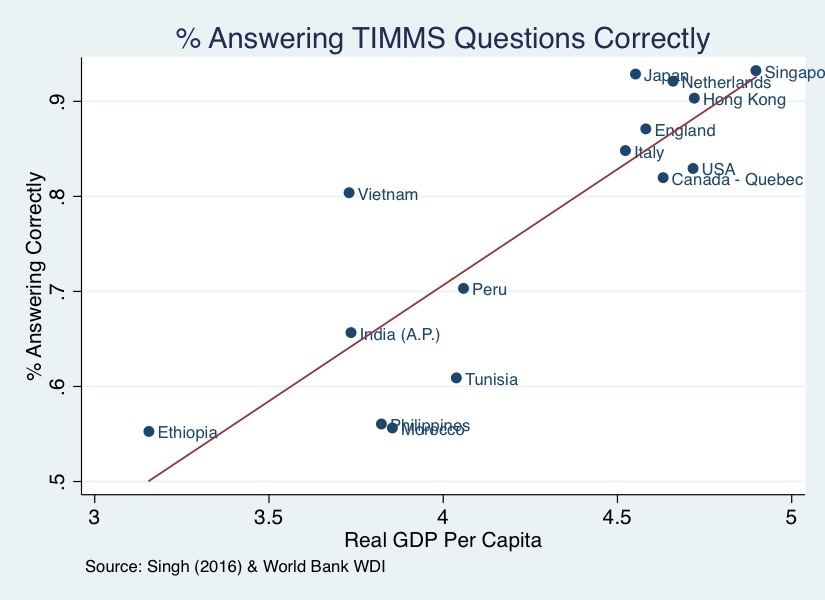

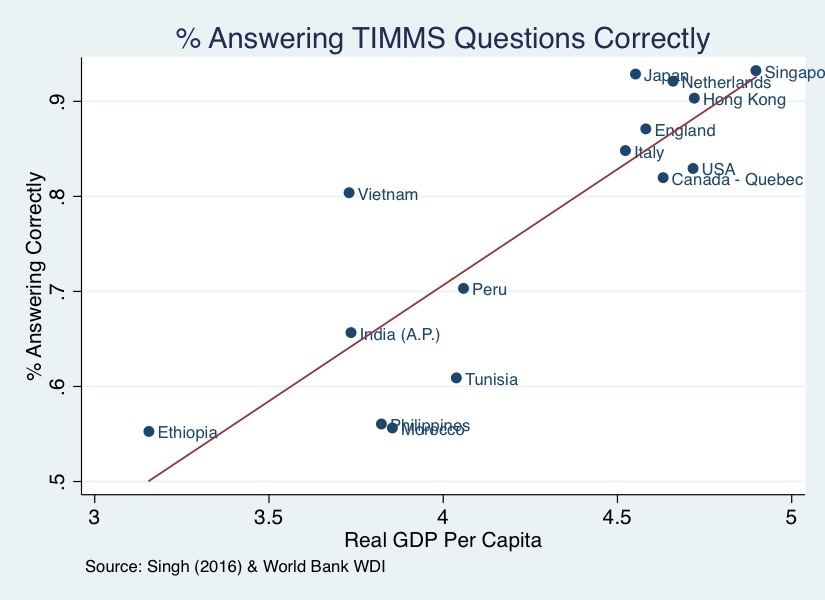

And this isn’t just on one test – other research by Abhijeet Singh has linked the Oxford Young Lives survey with the international TIMSS test, and again Vietnam massively outperforms the other low-income countries (see chart). Singh’s study shows that the advantage starts early, with Vietnamese children slightly outperforming those in other developing countries before they even start school at age 5, but this gap then grows each year. A year of primary school in Vietnam is considerably more ‘productive’ in terms of skill acquisition than a year of schooling in Peru or India, the paper finds. The question this research raises – and the Vietnam experience suggests - is: “Why is learning-productivity-per-year so much greater in some countries than others?” Or to put it more simply, why are schools so much better in some countries?

A new paper by World Bank researchers Suhas D. Parandekar and Elisabeth K. Sedmik shows just how difficult the “Vietnam effect” is to unscramble. With a statistical decomposition using available measured factors, the research suggests that a combination of targeted investments and “cultural factors” explain roughly half of the huge ~100 point gap between Vietnam and the other low-income countries on the PISA test.

The main factors are:

Investments

- Higher level of access to pre-school.

- Investment in school infrastructure, especially in cities and small towns.

And Cultural factors

- Students work harder – skip fewer classes, spend the same or more time in school, plus substantial extra time studying after school. Students are more disciplined and focused on their studies.

- Teachers appear to benefit from closer supervision of their work by the school principal and others.

- Parents may have an important role to play, by taking an active part in combining high expectations of their children, following up with their children’s teachers and contributing at school.

All this only gets us part of the way toward explaining the Vietnam phenomenon. The other half of the answer remains a Vietnam enigma, which we’re hoping the RISE Vietnam research team can help to unravel, ultimately possibly even providing some useful lessons for other low-income countries.

* The chart here shows the average proportion answering a TIMSS question correctly, averaged across 6 questions focused on the number content domain, taken from the 2003 TIMSS assessment